What’s the point of ever.fm? Why create recordings that change?

For thousands of years, songs were ephemeral and ever-changing. Songs were carried on the wind, growing like wildflowers wherever they landed. For thousands of years, songs were alive. Then, suddenly, they were turned to stone.

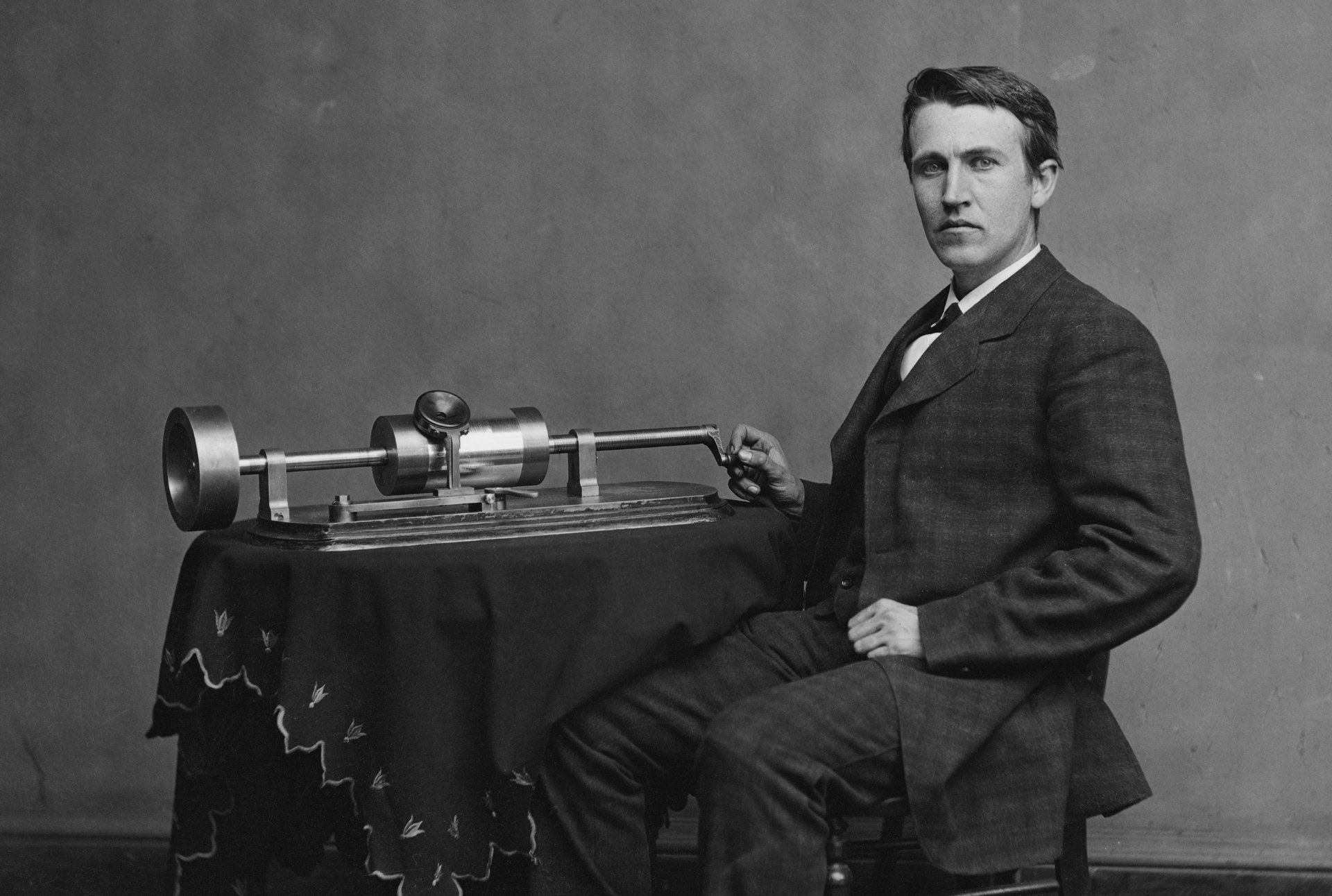

Edison may not have set out to create the record industry (after all, his machines were designed to replace stenographers, not musicians) but, nevertheless, the phonograph cast a powerful spell and there was no going back.

For thousands of years, songs were alive. Then, suddenly, they were turned to stone.

For the first century of its existence, the value of recorded sound followed a general upward trend, peaking in the mid-1990s with the convergence of cassettes and CDs. Then, in 2002, came Napster, the dawn of digital music sharing and two decades of economic tailspin for the music industry. Music-industry revenue declined sharply from a peak of $21.5 billion in 2000 to $6.9 billion in 2015. Since then, the industry has seen growth due to the mass adoption of streaming music services like Spotify, Apple Music and Tidal. However, the market value of a recording has changed forever: Spotify currently pays rights holders a fraction of a cent per stream. An artist must garner over 1,000 streams of a song just to buy a coffee.

An artist must garner over 1,000 streams [on Spotify] just to buy a coffee.

Success in streaming hinges on one thing: volume. Because of the way Spotify’s payouts are structured, artists with millions (or billions) of streams get a disproportionate cut of streaming revenues. That obscure band you binge-listened to all month long? They probably didn’t get penny from your subscription fee; it all went to Drake and Taylor Swift. While there is a movement among streaming services like Deezer and Tidal to adopt a user-centric payout model that might compensate artists more fairly, this approach has not been taken up by industry-leader Spotify.

“[Streaming] works if you’ve got thousands or millions of songs,” says Mark Mulligan of tracking firm MIDiA Research. “But if you’ve only got 20 or 30 or 100 songs then it doesn’t. You need scale of catalog to benefit.” Big artists get bigger, small artists get smaller. Without a drastic re-imagining of the recorded-music medium, the dream of the independent musician, fostered by 1990s-era optimism, is dead.

So let’s re-imagine it.

In the beginning was the wax cylinder. Then came a succession of physical formats: vinyl, 8-track, cassette, and CD. Finally, music was set free from its physical form with the advent of the mp3. Throughout this metamorphosis, one thing remains constant: recordings never change. Play, stop, repeat is all we ever get. It’s as true today as it was in 1877. One listen is like every other; it makes no difference if I listen now or later. There is little urgency or scarcity in this world of static music. More than ever, music has become the proverbial “wallpaper” in our lives: ubiquitous and forgettable.

But what if recordings could change? What if every listen was non-fungible? What if we realize the promise of disembodied music? Before the existence of streaming, blockchain and NFTs, this was unthinkable. Now, it may be a way to rebuild the value of music in the web3 era.

What if recordings could change? What if every listen was non-fungible?

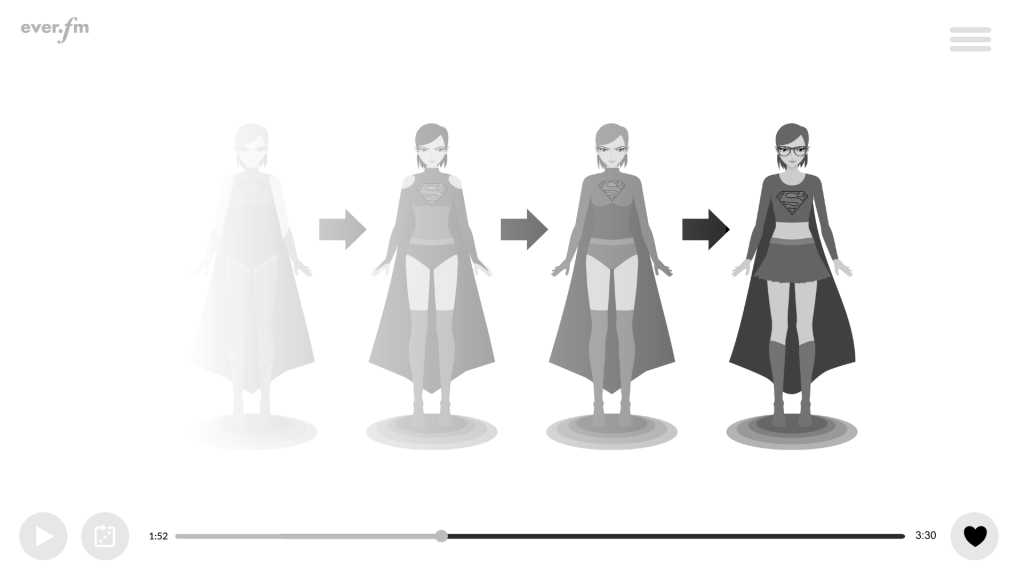

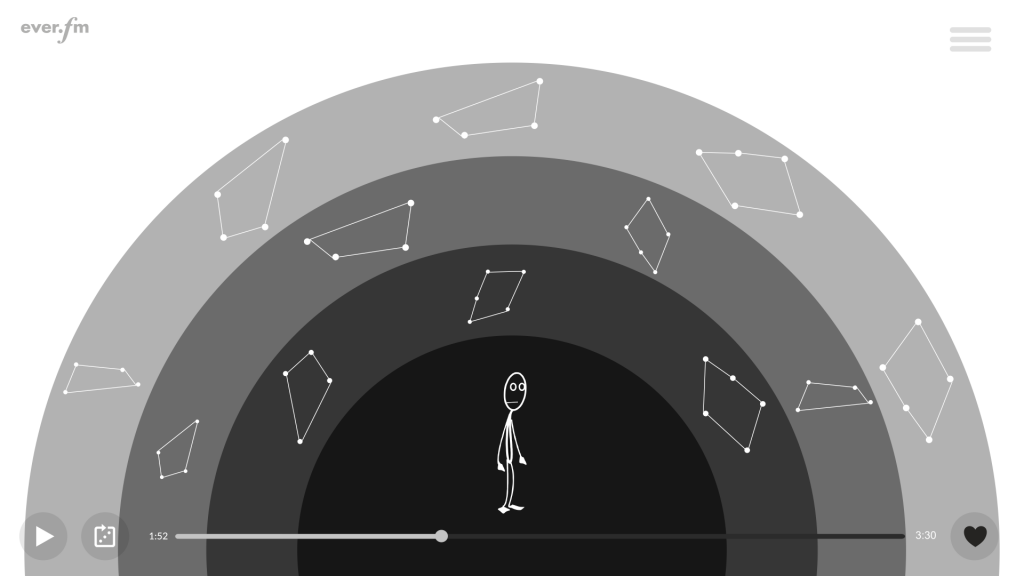

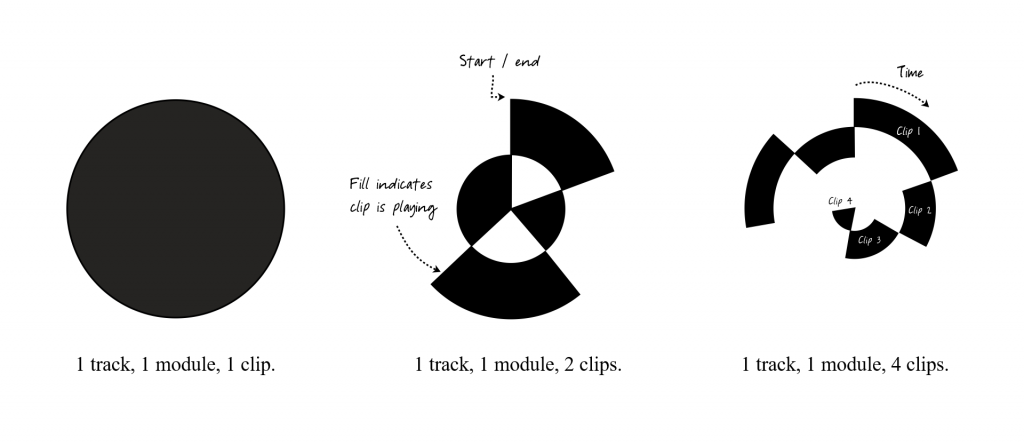

ever.fm has created a new format for recorded music, one in which a song is reborn every time it plays. It’s streaming music with superpowers. As a song plays, the listener can shuffle the inner workings of the music with the touch of a button, cycling through myriad possible renditions until they find the one they love. These renditions are generated on-the-fly by ever.fm using two ingredients: audio samples and playback rules, both of which are created by the artist. With every rendition comes new discoveries: never-before-heard combinations of instruments, new lyrics, harmonies, alternate takes and more.

On ever.fm, a song is the sum of its renditions the way a flip-book is the sum of its pages. There is no definitive version of a recording. Instead, every song is a collection of possibilities, and each possibility is an NFT that can be collected, shared and re-sold.

On ever.fm, songs are alive.